I recently accepted a commission to build a work desk in the Queen Anne style. This is for a very important client. In fact, I'm wondering if accepting this job is a conflict of interest as I'm also married to the client. I've already had to relearn those two fundamental axioms of running a business -- "The client is always right", and "What the client wants, the client gets." BTW, you can substitute "wife" for "client" if you like. These hold true either way.

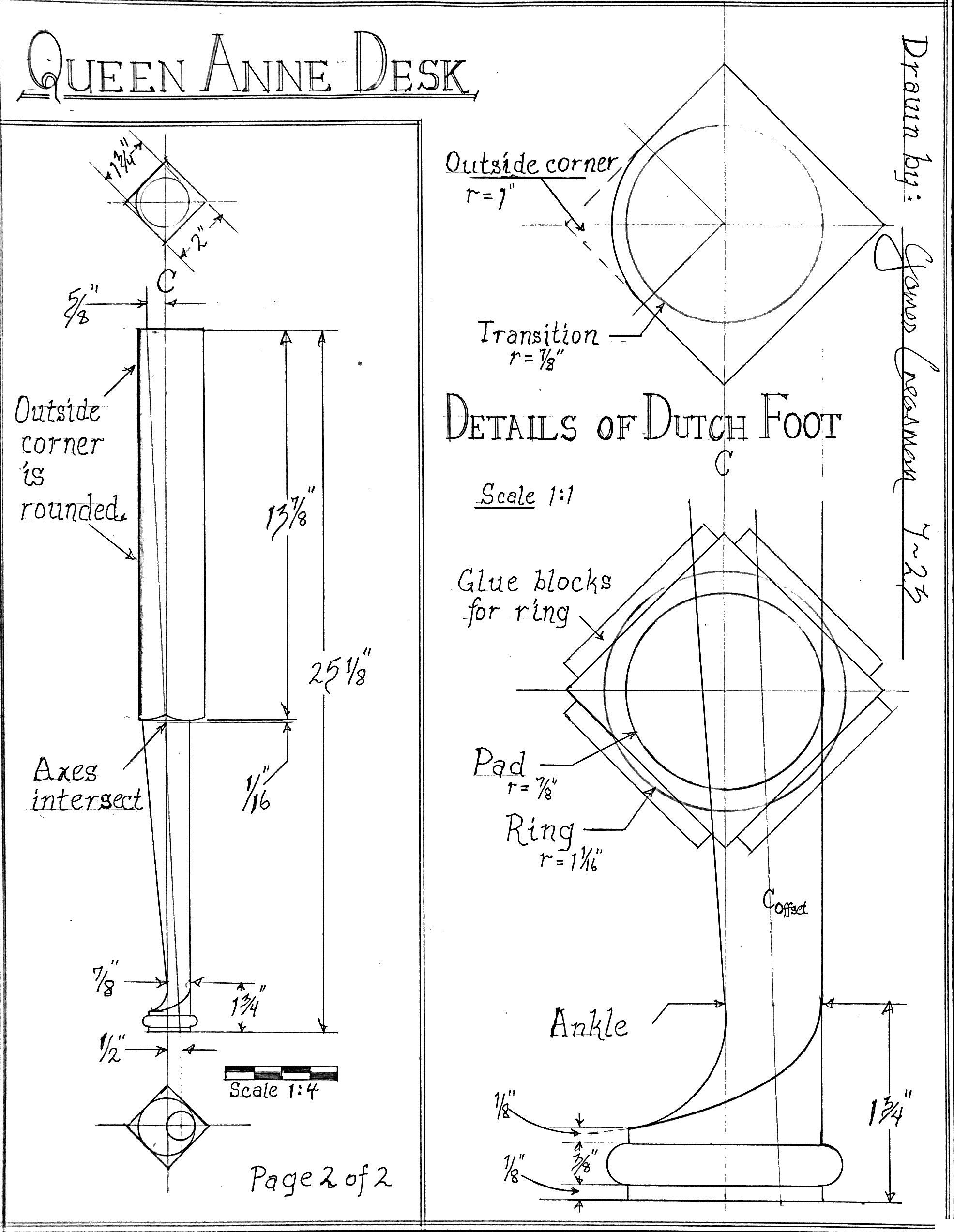

All kidding aside, I am looking forward to the project for the LOML. I'll document my progress here, and (hopefully) will wrap it up before the end of September. The first round of negotiations covered the basics -- mainly style and wood selection. These were pretty easy. She has another table that is Queen Anne style with Dutch feet turned that is cherry. The desk will be in the same style and fortunately I have some very nice cherry. It's air-dried, from old growth timber that was cut and milled around 50 years ago -- a woodworker's fantasy.

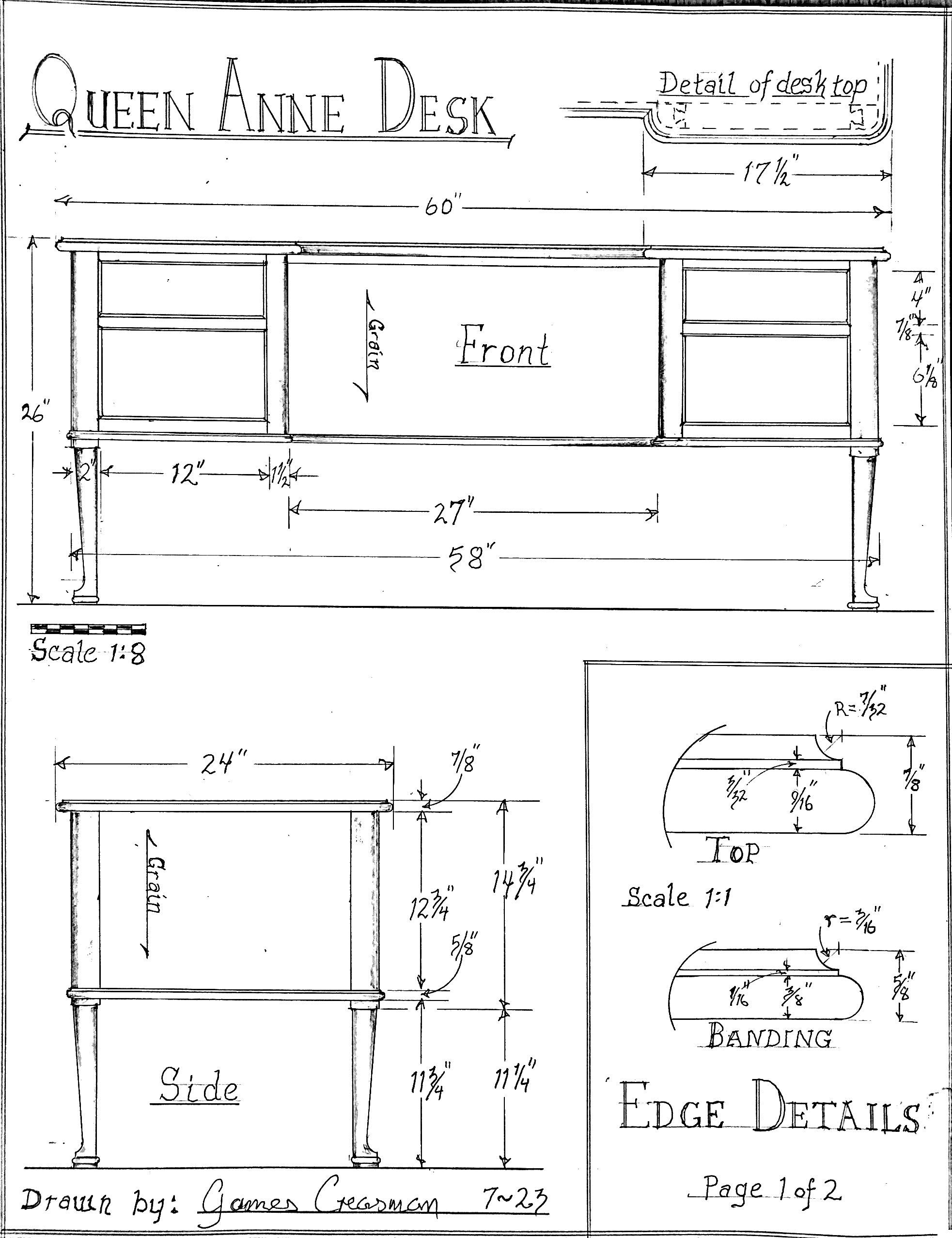

Next, we tackled the desk size. I have an adjustable desk for my day job. Using this we determined the optimal height for her would be 26". The width took a bit more consideration. She wants room for the chair to fit under the desk (at least up to the arms), enough room on each side to spread out her books, and a file drawer. I argued for symmetry, so we settled on an overall length of 60" with matching drawer fronts on either side. Depth is pretty standard at 24".

I spent time pouring over the books I have on furniture of this period and the internet to come up with a design. Even though my preference is to jump straight into building, I force myself to draw up plans. This makes me think through the process ahead of time so I don't "build myself into a corner." More importantly, it gives the client a visual they can sign off on. With that in mind I'll share the plans here so you can see where this project is heading.

I started working on the project a couple of weeks ago. The legs are turned and the case work is underway. If you're interested in the process continue to watch this thread for more updates as I have time.

All kidding aside, I am looking forward to the project for the LOML. I'll document my progress here, and (hopefully) will wrap it up before the end of September. The first round of negotiations covered the basics -- mainly style and wood selection. These were pretty easy. She has another table that is Queen Anne style with Dutch feet turned that is cherry. The desk will be in the same style and fortunately I have some very nice cherry. It's air-dried, from old growth timber that was cut and milled around 50 years ago -- a woodworker's fantasy.

Next, we tackled the desk size. I have an adjustable desk for my day job. Using this we determined the optimal height for her would be 26". The width took a bit more consideration. She wants room for the chair to fit under the desk (at least up to the arms), enough room on each side to spread out her books, and a file drawer. I argued for symmetry, so we settled on an overall length of 60" with matching drawer fronts on either side. Depth is pretty standard at 24".

I spent time pouring over the books I have on furniture of this period and the internet to come up with a design. Even though my preference is to jump straight into building, I force myself to draw up plans. This makes me think through the process ahead of time so I don't "build myself into a corner." More importantly, it gives the client a visual they can sign off on. With that in mind I'll share the plans here so you can see where this project is heading.

I started working on the project a couple of weeks ago. The legs are turned and the case work is underway. If you're interested in the process continue to watch this thread for more updates as I have time.